View The Catalog Here

RSVP For The Private View on Wednesday 27th March Here

Related Events: Artist Talk with Marcelle Hanselaar at The Last Tuesday Society – Monday 22nd April at 7pm. Tickets available via: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/artist-talk-marcelle-hanselaar-on-rebel-women-from-the-apocrapha-live-tickets-861520299407?aff=oddtdtcreator

We Are delighted to announce Marcelle Hanselaar’s second exhibition at 11 Mare Street

Rebel Women from the Apocrypha – by Mark Golder

The fifteen stories chosen by Hanselaar as the catalyst for this series come from the Judaeo-Christian biblical tradition, but she does not come to them from a faith background. Rather, these stories about powerful women caught her imagination over a period of decades, starting with hearing the tale of ‘Jezebel’ when she was at primary school and seeing a painting of ‘Judith’ by Cranach the Elder once she was an adult. What she liked about them was the no-nonsense, I-will-do-it-my-way attitude of the women. As the artist puts it, “These ancient imaginary narratives give us a much-needed energising subversiveness” in a world where deep-seated patriarchal attitudes are far from dead.

Hanselaar has called all the women ‘rebels’ and she has used the word ‘feisty’ to describe them. It truly sums up this assortment of women. Look at each print and then decide which of the various meanings of ‘feisty’ applies: lively, determined, courageous, spirited, spunky, plucky, strong-willed, or adamant. All these women are rebels against a male-dominated order of things, but Hanselaar is not thereby arguing they are all ‘good’ people. Even a fully paid-up feminist might question Herodias and Salome as role models when they connive at the murder of John the Baptist; and whilst Jezebel faces her death heroically she does have a previous history of murder and extortion.

Finally, some explanation of the word ‘apocrypha’ (which means ‘hidden’). There are three ways in which this term gets used. Firstly, there is the Apocrypha, with a capital A. This refers to books like ‘Judith’ which are only found in the Greek version of the Jewish Bible. Secondly, there are rabbinical commentaries on and elaborations of the Hebrew text. Thirdly, there is a very broad use of the term to suggest the appearance of folkloric elements within narratives. Hanselaar has continued in this tradition, adding her own ideas as an interpreter rather than as an illustrator in order to bring these stories to life for a predominantly secular audience in the early decades of the 21st century CE.

The Split, Adam and Eve

In Genesis/Bereshit the wife of Adam (‘Earth’) is Eve (‘Life’) and it is she who gets the blame for heeding the serpent and tempting humankind to disobey God. From this comes humanity’s expulsion from Paradise and sentence of death. She is also seen as of secondary value, being created from Adam’s rib. Hanselaar, however, picks up on something mentioned in later rabbinic commentary: that Adam soon realized that Eve was destined to engage in constant quarrels with him. Hanselaar brings out the erotic tension between Woman and Man. Adam lies on his back, the more passive position in sexual congress, and Eve pushes her stiletto heel into the wound from which she sprang. Here Woman takes control.

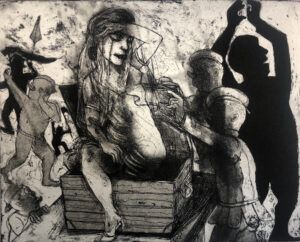

The Treasure, Sarai and Abraham

In the medieval period, Jewish lore expanded the story of Sarai (‘Princess’) who is the wife of the patriarch Abraham in Genesis/Bereshit. She is the most beautiful woman in the world and when her husband enters Egypt he is afraid men will kill him to obtain her, and so he conceals her in a chest. When the border guards search for contraband, Sarai emerges in a halo of brilliant light proceeding from her absolute beauty. Hanselaar turns Sarai into an image of life and light in a dark world. She steps out of the chest like Jesus from the tomb in Christian paintings from the Renaissance. This print could have been entitled: ‘Pulchritudo vincit omnia’ – ‘Beauty conquers All’.

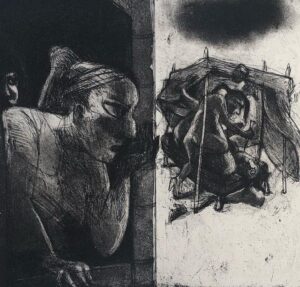

The Knowing, Sisera’s Mother

The territory between Egypt and Syria has been fought over for millennia. In the biblical book of Judges/Sefer Shoftim, we are introduced to Sisera’s mother, the gloating parent of a Canaanite general sent to defeat the Israelites. She yearns to see her son return home with his spoils, in her hybris being unable to imagine failure. Hanselaar shows her literally in the dark on the left hand side. She does not know that there has been a great Israelite victory and that Sisera has fled to take refuge in the tent of a Canaanite woman called Jael. On the right, the artist shows his moment of destruction at the hands of that woman as Jael hammers a spike into his forehead.

Vindication, Judith and Holofernes

The name Judith means ‘Jewish woman’ and in medieval times Jewish communities associated her story with Chanukah, the winter festival marking the salvation of Jerusalem and its Temple from assault by foreign enemies. When the Assyrian general Holofernes attacks her home town she visits him and seduces him… and when he is drunk she hacks off his head – which simply cries out for a Freudian interpretation. Professor Deborah Levine judges this Jewish hero to be “beautiful and bold, pious and violent, seductive and wise”. Hanselaar renders Judith as a femme fatale, looking like Louise Brooks in ‘Pandora’s Box’ (1929), who is about to start carving up the head of Holofernes.

Unguarded, Samson and Delilah

Men really ought to think with their brain rather than their crotch. In Judges/Sefer Shoftim, the Jewish hero Samson (‘He of the Sun’) meets the foreigner Delilah (‘She of the Night’) and falls heavily into lust. What he does not know is that she is working for the enemy: the Philistines. During their pillow talk Samson reveals that his strength lies in his hair. When she discloses this to the Philistines they enter the bedroom, cut off Samson’s hair and blind him. In the dark one man bores into one of Samson’s eyes with a spike. In the light we see Delilah holding aloft a tress of Samson’s hair and looking back as if in shock. She has ‘seen the light’ and seems to be saying to herself: ‘What have I done?’

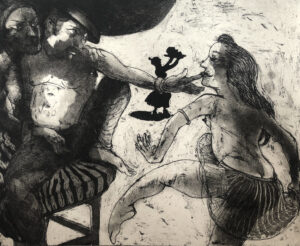

Beauty and the Beast, Salome

The story of Salome comes from the Christian Gospels and has all the trappings of grand guignol. A vengeful woman, Herodias, massages the crotch of her husband, Herod Antipas, as he watches the lascivious gyrations of her daughter and his step-daughter: Salome. Antipas stands for every man who thinks with his genitals rather than his brains, Salome for the bait of beauty, and Herodias for intelligent planning laced with malice. For in the background we see a servant holding aloft a plate on which sits the head of John the Baptist. Herodias, knowing her husband’s sexual weakness, has used Antipas’ lust for Salome, to get him to promise her the head of the prophet who accused the royal couple of incest.

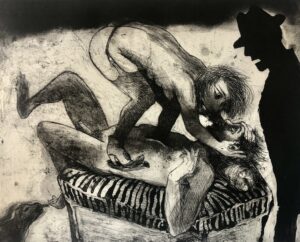

Temptation, Potiphar’s Wife

At the end of Genesis/Sefer Bereshit the Jews’ ancestors are in Egypt because of Joseph, the power behind the throne; but before he got there he was a slave jailed by his master after being accused of attempted rape by that master’s wife. Joseph is described as “well built and handsome” and in medieval sources the unnamed wife is called Zuleika (‘Lovely’). She wants him and he wants to remain faithful to his master. Eventually he runs away, leaving his robe behind, which she can use as evidence against him. Hanselaar plays up the sexual tension in this scene. Zuleika has an ape beside her (a symbol of lust) and Joseph is not totally immune to her charms… he looks back and holds his crotch.

The Taboo, the Witch of Endor

In 1 Samuel/Shmuel we meet the first king of Israel, Saul, who comes close to a nervous breakdown when faced by the Philistine threat. In order to see into the future he breaks his own law and visits the Witch of Endor, a necromancer who can raise the dead and ask their advice. She raises the shade of the prophet Samuel and he foretells the destruction of Saul. Whereas traditional portrayals show Saul and Samuel conversing, Hanselaar concentrates on the woman who has the power to summon the shade. The Witch is a tour-de-force, filling the left-hand side. Blindfolded, she sees what others cannot see, aided by the hallucinatory drug she carries in her right hand. Saul is her powerless suppliant.

The Secret, The Queen of Sheba

The artist shows ‘the arrival of the Queen of Sheba’ who, in the Jewish Bible, comes to test King Solomon’s wisdom; but Hanselaar uses details from later Jewish folklore, where, as the queen greets the Jewish king, she raises her skirt and he ungallantly remarks on her hairy legs. In 2017 Niamh McGuinne put on an exhibition entitled ‘Bristle’ and highlighted how female hairiness has been seen traditionally as deviant. Solomon may think he is wise and witty, but in Hanselaar’s rendering he is reduced to a shadow sitting on a stool. It is the queen who is in the light and triumphantly walking across the chequerboard floor. In this game of gender politics it is the queen who checks the king.

Genesis, Lilith, Queen of the Night

Lilith started life as a Babylonian demon (‘Night Monster’), but for Jews her story really takes off in the medieval period when the apocryphal Tales of Ben Sira mention her in detail. She is portrayed as Adam’s first wife, made from the earth as was he. She leaves both him and Paradise because she refuses to lie beneath him. For this shocking lack of female modesty and submission to male power she is turned into a winged demon who is a danger to new-born children. Hanselaar shows Lilith in mid-flight, her hair streaming in the wind. Around her body twines a serpent with a tail looking remarkably like a penis. In this imagery there is something of the witch as portrayed in centuries of European lore.

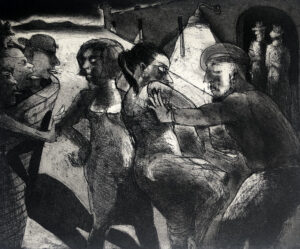

Condemned, Lot and his Daughters

For any feminist, the way that Lot treats his daughters when faced by the men of Sodom is at best questionable. In Genesis/Bereshit the Jewish family is living amongst foreigners. When angels visit Lot and he gives them shelter, the locals turn nasty and seek to sexually assault the visitors. Lot offers his daughters as a substitute. Ken Stone remarks that men within a patriarchal society are less shamed by the violation of women than by male-on-male assault. Hanselaar shows Lot forcing his daughters towards the men of Sodom. The body language of the daughter on the left suggests, “Don’t you dare touch me!”; and the daughter on the right seems confused at her father’s action and resistant.

The Last Laugh, Tamar

In Bereshit/Genesis 38, the widowed Tamar is a woman wronged. Judah, her father-in-law, prevents another of his sons from acting as a legal surrogate for his dead brother in order to ensure Tamar provides the latter with an heir. Only chutzpah enables Tamar to become pregnant by Judah himself. She sits by the roadside and entices him as he returns from a festival. Hanselaar captures the unromantic animal coupling by which this non-Jewish woman ensures her husband has progeny. A later rabbinic commentary condemns Judah, who receives the humiliation he deserves, and praises Tamar for her fidelity, which receives divine endorsement: she has twins, from one of whom King David is descended.

Looking back, Lot’s Wife

The second ‘Lot’ print in this series concentrates on the mother of the violated daughters. In Genesis/Bereshit she is nameless, but the latter rabbinic commentators called her Idit. The family have to flee from Sodom because the city is to be destroyed for even contemplating assaulting the angels. The biblical narrative mentions Lot’s wife breaking the divine command not to look back and, as a consequence, being turned into a pillar of salt. In the apocryphal literature the pillar becomes symbolic of ‘the unbelieving soul’. Hanselaar captures the liminal moment. Idit is looking back and a black shadow creeps over her like a shapeless but maleficent hand of Death which will ‘saltify’ her.

The Refusal, Queen Vashti

During the Jewish feast of Purim the biblical Esther is honoured for persuading her husband, King Ahasuerus, not to slaughter the Jews in Persia; but Hanselaar does not give us Esther. Instead she concentrates on the king’s first wife, Vashti, because of her daring defiance of a man with the power of life and death. When her drunken husband seeks to parade her before his guests, she refuses. The artist shows the queen from behind the veil of the women’s quarters halting her husband in his tracks. She goes on reading as he stamps his foot and rages. “She had dignity. She had self-respect. She said, ‘I’m not going to dance for you and your pals.’

The Untamed, Jezebel

In the first Book of Kings/Sefer Melachim, a military putsch backed by the Jewish prophet Elisha leads to the destruction of Israel’s royal family which includes the Sidonian, thus foreign, Queen Jezebel. In Jewish lore she is excoriated as the persecutor of the Jewish prophets and an epitome of injustice. Hanselaar concentrates on the moment of greatest drama: when her servants turn upon her and prepare to throw her out of the window to be eaten by dogs. The artist does not portray Jezebel as a victim, but rather as a woman used to command who goes to her death still trying to control the narrative of power. She is still applying her make-up – warpaint? – as her eunuch dares to touch the once untouchable queen.

Marcelle Hanselaar

Born in Rotterdam, the Netherlands and growing up in the formal atmosphere of a protestant, postwar country, proved, thanks to her drop-out/turn-on rebellion, a profound source of inspiration for the recurring subject matter in Hanselaar’s work; namely the fierce and sometimes troubled cohabitation with those raw desires, secret fantasies and uncultivated instincts and our functioning in a civil society.

Although she studied briefly at the Royal Academy of Arts in The Hague, her lust for adventure, guided by a quest for self-discovery, led her to years of travel, until, in the early 80’s she settled down in her studio in London where she still lives.Self-taught, she started out as an abstract painter before turning to figuration.

At the same time she became fascinated by etching, its harsh, bitten line seemed to perfectly suit her subject matter.As an artist Hanselaar looks for ways to express those illusive questions of who and what we are when the mask is off, and how we appear when the mask is on. The shock effect of her work lies in the contrast of combining her outspoken subject matter with the conventional medium of oil painting or etching.

Both her paintings and her prints display her delight and fascination with theatrical illusions and although often peppered with a biting sense of humor, the works reveals her own vibrant understanding of human nature, in all its animosity and fragility.